The shock, chaos and negotiations behind Thailand’s trade deal

South East Asia correspondent in Bangkok

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen US President Donald Trump made his dramatic tariff announcement on 2 April, nowhere was the shock greater than in South East Asia, a region whose entire world view and economic model is built on exports.

The levies went as high as 49% on some countries, hitting a range of industries from electronics exporters in Thailand and Vietnam to chip makers in Malaysia and clothing factories in Cambodia.

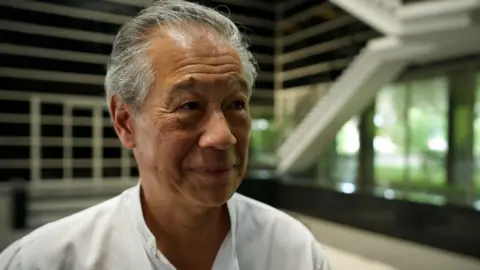

“I remember waking up in the morning. It was quite early, and seeing him standing there on the White House lawn with his board. I thought: ‘Did I see that right? 36%? How could it be?” says Richard Han, whose father founded Hana Microelectronics, one of Thailand’s biggest contract manufacturers.

Thailand, which was facing a 36% levy, now has a deal, like most of its neighbours, to reduce the tariffs to 19%.

The negotiations went down to the wire, finalised just two days before the deadline Trump had set – 1 August. It has been a fraught process getting there, and there is still very little detail about exactly what has been agreed.

BBC/ Lulu Luo

BBC/ Lulu LuoThe 10 countries in Asean, as the South East Asian regional bloc is known, exported $477bn (£360bn) worth of goods to the United States in 2024. Vietnam is by far the most exposed economy, its exports to the US totalling $137bn, making up about 30% of its GDP.

No surprise then that the Vietnamese government was first off the block to negotiate with the US, and the first in the region to do a deal to cut the punishing 46% rate Trump had imposed on them.

According to the US president, the deal cuts the tariffs to 20%, while he claims Vietnam will now impose no tariffs at all on any imports from the US. Tellingly, the Vietnamese leadership has said nothing about the deal.

There are no details, no written or signed documents, and some reports suggest Vietnam does not agree with Trump’s numbers. But they set the bar for other countries in the region.

Indonesia and the Philippines followed with deals reducing their tariffs to 19%, although neither country depends much on exports to the US.

Thailand does export a lot to the US. Last year they earned it more than $63bn, about one-fifth of its total exports. Thailand too should have been at the head of the queue in Washington, pleading for a reduction in the 36% tariff Trump had designated for it.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut Thailand is not Vietnam, a one-party communist state where critical decisions can be made quickly by a few leaders, with little need to worry about the opinions of businesses or the public.

Rather, like South Korea and Japan, whose deals came after much wrangling despite them being staunch American allies, Thailand too has to contend with domestic politics and public opinion. Thailand also has a weak and fractious coalition government, beholden to a range of vested interests.

Worse still, decisions it took which were entirely unrelated to trade angered the US side.

In February it sent 40 Uyghur asylum-seekers who had been stuck in Thailand for more than a decade back to China, defying warnings by the US Secretary of State Marco Rubio. One Thai trade official told the BBC the US negotiators were still bringing up the Uyghurs as a grievance at tariff talks in May.

Then a regional army commander filed a lèse-majesté complaint against a US academic, resulting in him being jailed and then forced to leave Thailand. So, far from being at the front, Thailand found itself at the back of the queue.

The other difficulty facing the Thai trade team was what the US was asking for in return for cutting the tariff rate, in particular access to Thailand’s agricultural market, which is heavily protected.

Food is big business in Thailand. CP Group, one of the world’s agribusiness giants, is the biggest company in the country. This US demand was painful for Thailand.

“Vietnam opened a Pandora’s box,” says another Thai trade official. “By offering zero percent tariffs on all US imports, they make it hard for those of us who can’t easily open up all sectors to US competition.”

BBC/ Lulu Luo

BBC/ Lulu LuoThree hours’ drive from Bangkok, in Nakhon Nayok, Worawut Siripun keeps 12,000 pigs – an important business in Thailand; Thais eat a lot of pork. He is active in the Thai Swine Raisers Association, and has been lobbying against eliminating tariffs on US pork.

“US farmers produce on a much bigger scale than us, and their costs are lower. So, the price of their pork will be lower, and domestic farmers won’t be able to survive.”

Access to the agricultural market was also a sticking point in negotiations with Japan, which sought to protect its rice farmers, and continues to be one of the main hurdles with India.

In Thailand, it is presumed that agribusiness giants like CP have also been lobbying against US demands to open up other sectors like poultry and corn. There have been fractious meetings between the trade team and cabinet ministers after every round of tariff talks in Washington, the BBC understands.

BBC/ Lulu Luo

BBC/ Lulu LuoBut on the other side are Thailand’s manufacturers, who represent a much larger contribution to GDP than agriculture. They badly needed a deal.

“If we get 36% then it’s going to be terrible for us,” said Suparp Suwanpimolkul, deputy managing director of SK Polymer, before the deal was announced. The company makes a bewildering array of components from rubber and synthetic materials, for washing machines, fridges, air conditioners.

“I guarantee you would find at least one of our products in your home,” he said.

SK Polymer was founded by Suparp and his two brothers in 1991. Its story is the story of modern Thailand, originating from their father’s small family business, but riding the explosive growth of global trade which has been the foundation of Thailand’s economy.

They are an integral part of a complex supply chain, where their products join other components from multiple countries to make consumer, industrial or medical goods for export. About 20% of the company’s income comes from the US, but the number is much higher when products which contain its components are included. The Trump tariffs have thrown a spanner in the works.

“We have small margins,” said Suparp. He said they could still manage with tariffs up to 20% or even 25% by cutting costs. When he spoke to the BBC, before the deal was announced, he said the uncertainty was the biggest challenge: “Please – to our government, just get the deal, so we can plan our business.”

BBC/ Lulu Luo

BBC/ Lulu LuoA 20% levy is also palatable for electronics manufacturers, a big industry in Thailand.

“If all of us in this region end up with around 20% our buyers won’t seek alternative suppliers – it will just be a tax, like VAT, for US consumers,” says Richard Han, CEO of Hana Microelectronics. The company makes the basic components that go into everything in our digital lives: printed circuit boards, integrated circuits, RFID tags for pricing.

Mr Han says only about 12% of his products go to the US directly, but like SK Polymer the proportion that goes indirectly, as part of other manufactured goods, is much higher. But it is not just the tariff number that worries him.

His concern is trans-shipment, the US charge that China is avoiding tariffs by routing its production through South East Asia. Already Vietnam, according to President Trump, will pay 40% – double the new tariff rate – on goods the US judges to be trans-shipped.

Both Thailand and Vietnam saw foreign investment increase significantly after tariffs were imposed on China in the first Trump term, and their exports to the US rose as well. Some of that was Chinese companies moving production; some was products using a lot more Chinese-made components. And they are not just from China.

At another electronics manufacturer, SVI, robots glided up and down the assembly line bringing hundreds of tiny components to assemble circuit boards in machines that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. A quick look at the labels showed the components came from Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and China.

SVI makes security cameras, bespoke amplifiers, medical equipment, to whatever specification their customers, who are mainly in Scandinavia, want. Thailand’s vital manufacturing sector is part of an immensely complex global supply chain which is almost impossible to rearrange to meet the US president’s demands.

Under WTO rules a product is considered local if at least 40% of its value is added in the local manufacturing process, or if it has been “substantially transformed” into a new product, the way an iPhone becomes something different once it has been assembled.

BBC/ Lulu Luo

BBC/ Lulu LuoThe Trump administration pays no heed to WTO rules, and it is not clear what will be counted as trans-shipped, but Mr Han fears this could prove a bigger problem for Thai companies than the standard tariff rate if the US insists on more local components, or fewer from China.

“South East Asia relies very heavily on China,” he explains. “China, by far, has the largest supply chain for electronics and many other industries, and they are the cheapest.

“We could buy materials from another part of the world. It would be a lot more expensive. But it would be virtually impossible for Thailand or Vietnam or the Philippines or Malaysia to get a very high threshold, say 50-60%, made within that country. And if that is the condition to get the US certificate of origin, then nobody’s going to get the certificate of origin.”

For the moment very few of these details have been revealed. Despite President Trump claiming he has got zero percent tariffs for US goods coming into the Philippines and Indonesia, both those countries have said this is not correct, and that much still needs to be negotiated.

For the Thai government, having started so late, and struggled to meet US demands, just getting a deal will have been a relief.

They will worry about how to make the deal work later, as the details are worked out, which typically takes years. And in that, they are far from alone – rich and developing economies alike are scrambling to keep up with Trump’s mercurial tariff policy.

“At some point this has to stop. Surely it has to stop?” Mr Han says. “The trouble is, we don’t know what the rules of the game are going to be, so we’re all milling around, just waiting to find out how to play the new game.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/0a95/live/be18aa60-6e72-11f0-89ea-4d6f9851f623.jpg

2025-08-01 02:35:53